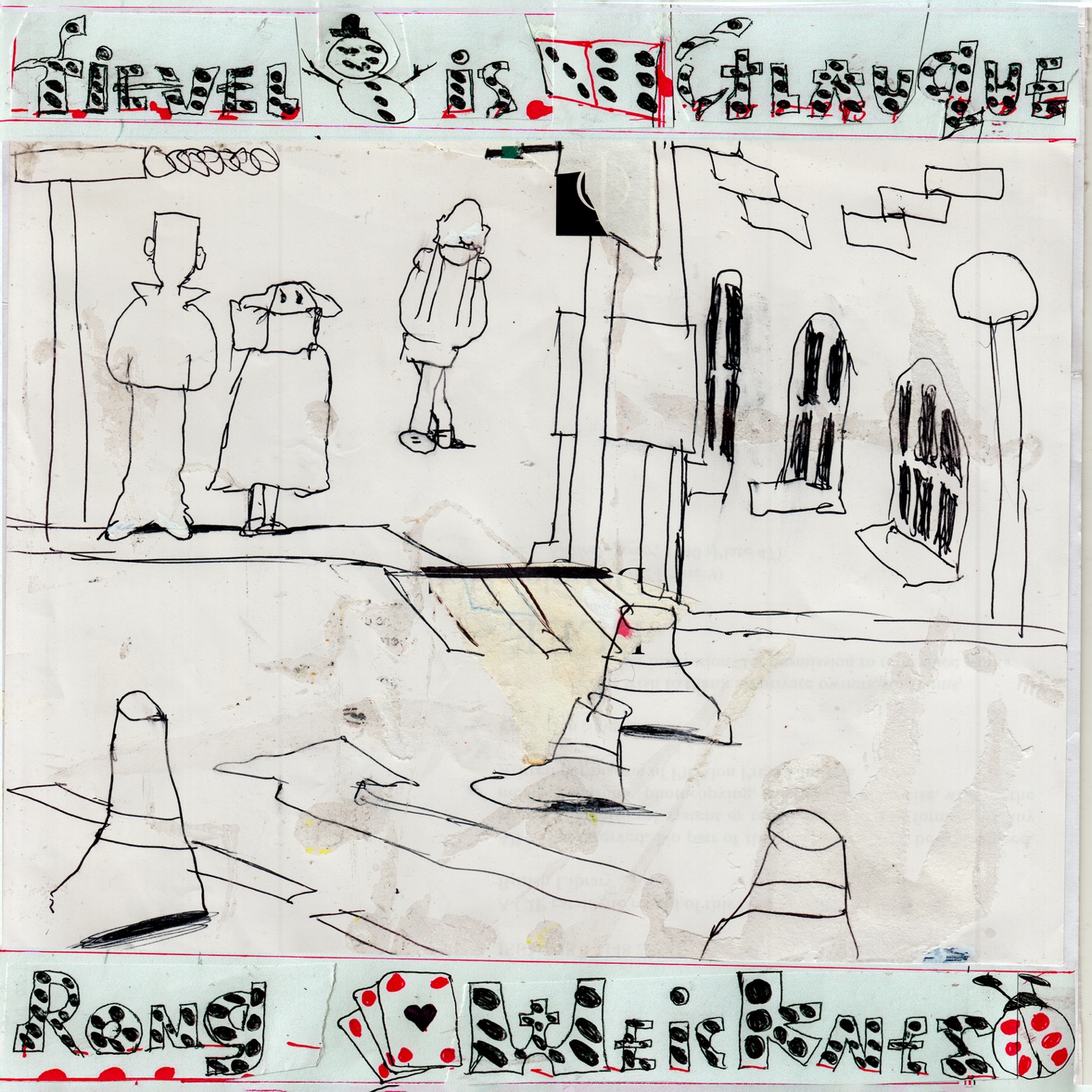

Zach Phillips of Fievel is Glauque talks Representation, Reworks, and New Record ‘Rong Weicknes’

“In this record…there are gaps…but they are filled…with images.” In Richard Foreman’s “City Archives,” he narrates such a line over the puzzling, converging layers of visual stimuli—bodies and faces stacked atop each other, cameras swiping through varied liminal scenes. The quote also appears on “Would You Rather?”, an interlude on Fievel is Glauque’s newest record, Rong Weicknes, a fitting elucidation for the winding, textured intricacies that compose the album’s music.

On the third LP between NY-based Zach Phillips and Belgium-based singer Ma Clément, along with their international band of frequent collaborators (Thom Gill [guitar], Logan Kane [bass], Daniel Rossi [percussion], André Sacalxot [saxophone, flute], Gaspard Sicx [drums], and Chris Weisman [guitar, electric sitar]), the band injects this sense of layered multiplicities, finding new modes and processes of representation. Part of that involved a new technique of recording in what Phillips calls “live-in-triplicate,” a model structured as (1) an initial recording, (2) a duplicate, and (3) an improvisatory.

“Part of the energy behind that is attention paid to representation, which in my experience, gets overlooked a lot, even in avowedly experimental music,” Phillips tells me. “To my mind, when you’re making a recording, the object that you’re working on is the recording, not the music that’s being represented in the recording. Obviously, the music that is being represented in the recording is the subject of the recording, but the object that you are working on is a recording.”

The implementation of the live-in-triplicate technique arose from both the band’s setting and first-time collaboration with engineer Steve Vealey. Recorded at The Outlier Inn in Upstate New York, Phillips emphasizes a shift in their approach to the project. “We had been rigorously adhering to this DIY-mentality…but our manager Lucas [Myers] was like there’s this place Outlier that I think would be really great. The second we looked at it we were like, ‘Can we please do it there.’” Phillips underscores the quality Vealey brought to the process in conjunction with the value of the recording studio and the level of preparation from each musician.

Rong Weicknes also marks the band’s first album release under Fat Possum Records—though it is far from Phillips’ first relationship with labels. Leading OSR Tapes, Phillips was significant in releasing eclectic independent music during the 2000s and 2010s, including projects by Ruth Garbus and Weisman. With this background, he found an interrelation between his work at OSR and his relationship working under Fat Possum.

“I’m completely driving blind and I always have been…I’m perpetually confused and that has been true from when I was doing the DIY thing exclusively and it’s certainly true now that we’re working with a team. [The label’s support] was absolutely unavoidable for practical and financial reasons. Because the finances of this band have been very difficult—it being international, we prefer this large format band of 6 or more people whenever we do a show. It’s a lot.”

He reminisces on the occasional absurdity of leading the label. “Every time I did a group of releases on OSR, it was literally all of my money. It was like, ‘Oh, I’ll still have a grand or two left, so I should look for something else to release.’”

Particularly influential from the OSR Tapes period is Phillips’ work in the duo Blanche Blanche Blanche (BBB) with Sarah Smith. “Ma and I both have this feeling that, among other things, we’re students of BBB. There are certain things that Sarah and I were able to do that were very unconscious. Even though I was there doing it, I don’t know how it happened.”

On “Love Weapon,” the album’s second single, the band reworks a 2012 track from BBB’s 2wice 2wins, injecting new harmonies, Clément’s airy vocals, and an extravagantly glistening instrumental outro spotlighting Sacalxot’s saxophone. Phillips mentions German playwright Franz Xaver Kroetz’s practice of rewriting the endings to his older plays. “I don’t think that’s what we’re doing but your question reminded me of it as something I admired”; it’s a testament to the rapidity at which Phillips can conjure up niche, yet poignant meditations on life and craft.

His process does seem to call upon the unconscious creation evoked in Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa’s 1934 poem “There Was A Rhythm To My Sleep,” which reads, “When I woke it was lost. / Why did I leave that abandonment / of myself, in which I lived?” Phillips, who lists Pessoa as a major influence on his creative and personal development, seems to be searching for a score—or order—derived in a state of abandon.

Pessoa appears more directly in the form of the song title, “I’m Scanning Things I Can’t See,” pulled directly from one of his poems. On the album, the track, originally released in August 2023, is upgraded with a more spacious feel and crisper sound, as well as a prominent mid-song saxophone solo and tinges of flute. Around 2:00, Clément’s voice balloons out, emerging through the band and drawing listeners even closer.

The album’s closer, “Haut Contre Bas,” is another reinterpretation of a Phillips cut, this time from his project titled GDC. The track morphs the warped electronic elements of the original and locates them in new guitar riffs, with Clément hypnotically riding along overlapping grooves.

Other standouts include “Great Blues,” flourishing with soaring vocals from Clément and an underlayer of hurried instrumentation. On “Kayfabe,” her voice mutates through stages of thick speaking, elasticized yawning wails, and chomping noises. The attention to vocals and language remains one of the band’s main musical concerns. Phillips configures Lacan’s Lalangue in conversation with the construction of music’s language—though he’s quick to underscore that Lacan is not his choice psychoanalyst, instead mentioning British psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott. “Ma and I pay a lot of attention to rhyme, non-rhyme, half rhyme, internal rhyme, assonance, alliteration, idiom, all of this stuff. So there’s a dimension of letting something unconscious happen through that, through the formal and Lalangue properties of the music and lyric.”

Phillips has also previously likened the creation of music to that of prayer, calling to mind the “dimension of courting and consulting the known.” He expands on that conception further, breaking down the relation into two parts. 1. “Being vulnerable to your unconsciousness and getting information from things like speech or automatic writing.” 2. Game-like attention to gesture, “allowing yourself to follow impulses and make moves that are not necessarily informed by critical thinking, but you assume them to be final.”

It is thus apt that the band describes Rong Weicknes as the “loosest” and “tightest” record they’ve ever made, considering the aspect of “impossibility” Phillips mentions in switching between these valences of prayer-like creation. Much of these philosophies, and their manifestation on the album, feel Borgean, with paradoxical inclinations, attention to language, and a willingness to follow each other down musical mazes. It is what makes the music so exciting to hear: a commitment to the noncommittal.

While there are clear elements of jazz, French pop, 70s rock riffs, funk, and a grab bag of other influences, it gels without force. Appreciating the cultural shift in viewing genre as an amorphous zone for similar relationalities—rather than a place for pigeonholing artists—Phillips shares his hesitancy to phrases like “avant-garde jazz” which are often attached to Fievel’s music.

“I don’t like the term avant-garde because it’s a military analogy and I don’t like the idea that we’re in the trenches. I want to be out of the trenches…My personality is like, I’ve already been beaten, I’ve assumed I’ve lost, so I can’t be on the frontlines…The way people say that is to compliment something unusual and embrace having an unusual orientation…so I appreciate it as a compliment. As for jazz, I’m uncomfortable claiming an affiliation with it. A lot of people in the band come from a jazz background. Identifying as a jazz musician is culturally and politically complex. I do not have any background playing jazz other than studying some standards and listening to and respecting the history of that music a great deal…As a matter of genre, who gives a fuck. It’s grindcore.”

While Phillips continually finds new ways of improving himself and his craft, he reveals a continual wrestling with his relationship to live performance. (Previously, he described his difficulties reconnecting with the act of creating music after touring with Stereolab in 2022.)

“There’s a lot that you can’t control and sometimes you can’t hear each other that well. You have to get used to the environment…When I’m on stage, I play a lot of little games with myself. It would probably be better if the way I navigated gigs was by [applying] everything exactly in a somewhat rote way. I take a lot of risks when I’m playing and I mess up a lot. To me, performance is really about whether I can make good mistakes and then incorporate them into the bigger picture of what everybody’s doing. Bring things out in the music, remove things, complicate things. Can I make gestures and then parry quickly enough to make that gesture make sense.”

Though they have not disclosed plans for a multi-city tour, the band recently announced two shows in February of 2025 in New York and Los Angeles. As headliners, the band will look forward to hopefully regaining some more control and comfort within their performance. In their announcement of the shows on Instagram, they added, “We are weird, international, obsessed with not repeating ourselves, and don’t operate normally.” It’s a sharp and fitting summation for Fievel is Glauque, a band whose peculiarities and dedication to transformation make them so fun to watch.

Rong Weicknes is out now via Fat Possum Records. For more information about the band’s new music and upcoming shows, check out their website here.